Conjuring up words that were never spoken

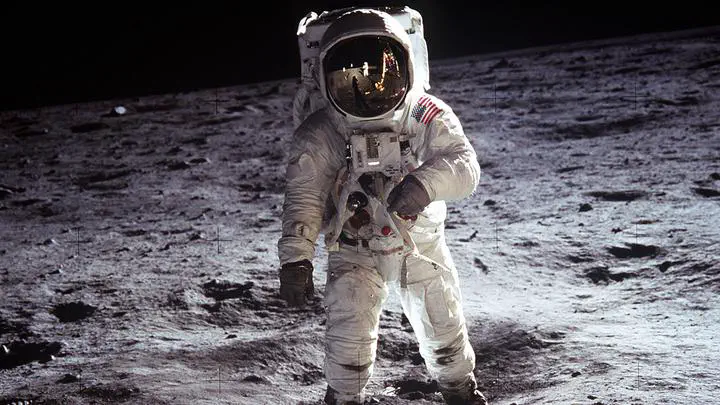

Remember this one?

Do you remember this famous quote, starting at 00:15s?

This was Neil Armstrong, landing on the moon on July 20, 1969. But hold on, what is he saying exactly? Let’s listen to the first part of his famous quote:

Is it:

- “one small step for man”, or:

- “one small step for a man”?

Both transcripts are grammatically viable, but they mean different things. In (1), “man” is used as a synonym of “mankind”, while in (2) “man” is used with the meaning of “person”. Only the second transcript actually fits the remainder of the quote ("…one giant leap for mankind") and Neil Armstrong himself also claimed that he had uttered the second version (Baese-Berk et al., 2016). But how come people miss the “a” in the recording?

Speech is messy

When we talk, we don’t produce ‘spaces’ between words. Instead, we join all the words together, producing a connected stream of sound. This is especially true for function words, like “a”, “or”, “for”, and “and”. It is quite likely that Neil Armstrong intended to say “for a man”, but in stringing together the sounds for the words, the “a” was ’lost’ in articulation. This is what speech scientists call ‘reductions’ in speech.

Taking speech rate into account

OK, so the “a” is ‘reduced’ in the original pronunciation. But human perception is not only determined by the input signal alone. Instead, it is heavily context-dependent, taking into account such contextual factors as who is talking, why he is talking, and even how fast the speech is likely to come in!

Evidence for this comes from ‘context effects’, whereby for instance the acoustic characteristics of a preceding sentence can influence what you hear next. Let’s take speech rate for example. If you hear someone say “That’s one small step…” at a really fast tempo, it is very likely that the next few words will be spoken at a fast rate too. And conversely: if someone happens to speak at a slow rate, the next few sounds will likely be slow too. This means people are likely to interpret the next few sounds in line with the speech rate of the preceding sentence.

Conjuring up the “a”

Now let’s see if we can make the “a” in Neil Armstrong’s quote appear and disappear by playing around with the speech rate of only the surrounding speech. Note that we’re not changing anything about the “for (a)” part of the audio clip (highlighted in red in video below). All we’ll do is speed up (compressed by 2) or slow down (compressed by 0.5) the surrounding parts of the recording. Do you hear “for man” or “for a man”?

Click here to access the audio from the video

ORIGINAL CLIP

CONTEXT SLOWED DOWN

CONTEXT SPED UP

What happened there?

Most listeners will report hearing “for man” in the bottom clip, with the slowed-down context, but “for a man” in the top clip, with the sped-up context. Notably, these clips have the exact same “for a” part; they only differ in the speech rate of the surrounding context. The slow context makes listeners predict that the “for (a)” part was uttered at a slow rate too. But this critical “for (a)” does not contain a really slow “a”, so people ‘miss’ the function word. However, in a fast context, listeners expect the critical “for (a)” to be uttered at a fast rate. This “for (a)” does indeed (kinda) match a really fast and short “a”, so people are more likely to report hearing “for a man”.

Why is this important?

Context effects abound in perception, and so they also surface in speech perception. People interpret speech sounds differently depending on the surrounding speech rate, formants, and perceived pitch. But even non-acoustic aspects of the context are taken into account: people hear a sound differently depending on the talker’s gender, the talker’s hand gestures, one’s own preceding speech, and there’s even reports that a stuffed toy seen in the background can change what you hear (Hay & Drager, 2010). All these phenomena together shape human speech perception. So if we want Automatic Speech Recognition (the Siri’s, Cortana’s, and Alexa’s of this world) to approach human-like behavior, we need to know each and every aspect that defines what words we (think we) hear. Oh, and apparently it also helps extraterrestrial communication.

Relevant papers

(2017). How our own speech rate influences our perception of others. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 43(8), 1225-1238, doi:10.1037/xlm0000381.

(2017). Accounting for rate-dependent category boundary shifts in speech perception. Attention, Perception & Psychophysics, 79, 333-343, doi:10.3758/s13414-016-1206-4.