How strong is the rhythm of perception?

With 25 teams from around the globe, we tested if a simple acoustic rhythm guides your auditory perception. Check out what we found in “How strong is the rhythm of perception? A registered replication of Hickok et al. (2015)”

First: some time travel

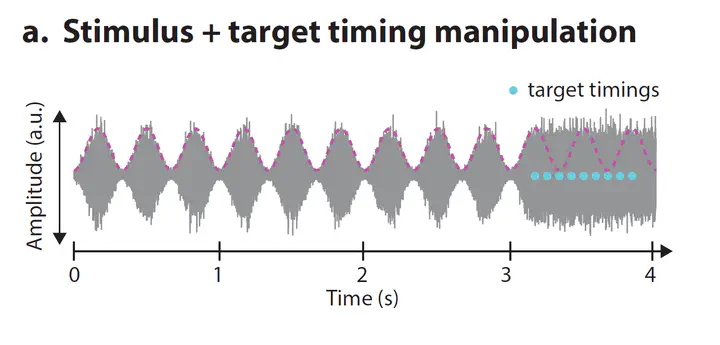

In 2015, Greg Hickok, Haleh Farahbod, and Kourosh Saberi (HFS, for short) published a paper in Psychological Science, entitled “The rhythm of perception: entrainment to acoustic rhythms induces subsequent perceptual oscillation”. They had come up with a clever new paradigm to test if listening to a short rhythmic noise stimulus would guide subsequent auditory perception. As illustrated in the figure above, they played noise that rhythmically fluctuated in amplitude (loud, quiet, loud, quiet, etc.) for 3 seconds. After those 3 seconds, the noise stopped fluctuating, staying at a fixed level. Importantly, HFS sometimes hid a very short and hard-to-hear beep inside this steady-noise part. This beep, if present, could be played at any of 9 different time points (the lightblue dots in the figure above). Their participants were instructed to say if there was a beep inside the noise, yes or no.

Interestingly, the detection accuracy of these participants fluctuated with the rhythm of the preceding noise signal. Keep in mind that the noise has exactly the same level at any of the 9 blue time points. Therefore, there’s no particular reason why you’d be better at detecting the beep at time point 3 compared to time point 5, for instance. Nevertheless, that’s what HFS found: people had low accuracy at time points 1, 5, and 9 (when the noise would have been high, if the preceding rhythm had continued) and better accuracy at time points 3 and 7 (when the noise would have been low). This suggests that the human brain aligns its perception to acoustic rhythms, with this perceptual rhythm continuing even when the acoustic rhythm itself has already ceased.

What’s the problem?

The beauty of HFS’s paradigm and their impressive results made a big impact on the field. Therefore, several researchers adopted the paradigm, hoping to find the same effect. However, even though some succeeded, many did not find the same outcomes, despite using a similar or even the same methods as HFS (inside info: my own attempt failed too, actually). Moreover, HFS had tested only 5 participants, and their conclusions rested on only 10% of their data. Together, this raised questions around the reliability of the reported effect and if the results actually hold up. Therefore, Molly Henry and Jonathan Peelle initiated a multi-lab replication attempt, inviting research groups from around the globe to join the effort.

What did you do?

Molly and Jonathan received the audio files from HFS, made them freely available to all teams, together with a ready-made experiment protocol. All we had to do is find some people who had the guts to listen to 2,250 (!) of these audio files and each time press a button indicating if they heard a beep, yes or no. All in all, 25 teams joined forces, together testing 151 participants, collecting over 335,000 button presses in total!

And? What came out?

It replicated!

In the topright panel (a) of Figure 3 above, you can see that the detection accuracy across all participants (the thick black line) indeed fluctuated at the rhythm of the preceding noise signal! However, in panel (c) below it, you can also see that individual participants varied a lot in their ‘perceptual rhythm’: some indeed showed evidence for the effect (large positive effect sizes), but many only showed a small effect, or none at all (or even in the opposite direction). It’s only when analyzing across participants that we see reliable evidence for a rhythm in auditory perception.

Why is this important?

This multi-lab collaboration is, in my view, an excellent example of open team science. It ticks all the boxes: all methods were pre-registered; the study was externally reviewed before data collection started; data acquisition, analysis, and archiving is fully transparent and open; state-of-the-art analyses were applied; and working together with teams from across the globe was so much fun! Even independent from the outcomes, this team science project on its own already demonstrates how science should be done.

The fact that the effect replicated was actually a bit of a surprise to me. The individual variability shows the effect is pretty fragile: only when testing lots of people, who each take part in multiple sessions, making up 1000s of trials, do we indeed find evidence for a ‘perceptual rhythm’ in auditory perception. This also raises questions about the theoretical implications of this finding as well as the suitability of the paradigm.

That is: if we play highly artificial noise signals to 1000s of people, we find evidence for a ‘perceptual rhythm’. But few sounds in real life are this rhythmic: music and speech are both pseudo-rhythmic auditory signals with certain temporal regularities, but they are no way near as regularly rhythmic as these noise sounds. Does the ‘perceptual rhythm’, as demonstrated here, then actually have any implications for our understanding of human music and speech perception?

Moreover, imagine you want to run an experiment on human auditory perception. Would you use this paradigm? If your resources are limited (and they often are), you’d not probably not, right? You’d need to test lots of people, in multiple sessions, each involving hundreds of trials… and even then you’ll probably only find a small effect. Therefore, even though this team effort was indeed successful, it at the same time also reveals the limitations of the paradigm, as originally presented by HFS.

Full reference

The full citation, open access PDF, and all data are publicly available from the links below:

(2025). How strong is the rhythm of perception? A registered replication of Hickok et al. (2015). Royal Society Open Science, 12(6), 220497, doi:10.1098/rsos.220497.