A foreign accent in your hands

The timing of your hand movements may give away your native language. Read all about this ‘kinematic accent’ in our latest paper in Open Mind.

Published!

In 2020, we set out on a team science adventure. Now, 6 years later, the results are finally out. Our new paper “Foreign language learners show a kinematic accent in their co-speech hand movements”, written jointly by Hans Rutger Bosker, Marieke Hoetjes, Doenja Hustin, Wim Pouw, and Lieke van Maastricht, was published in Open Mind, a Diamond Open Access journal. The full text and all supporting data are publicly available from links at the bottom of this post.

What’s it about?

When you learn a new language, you don’t only need to learn new words and their meanings. You also need to know how to pronounce them correctly, including for instance which syllable is stressed. For example, Dutch learners of Spanish need to learn that the Spanish word pro-fe-SOR has stress on the last syllable, even though in Dutch the same word has penultimate stress: pro-FES-sor. Stress is notably hard to get right in a foreign language, explaining in part why native listeners can hear a foreign accent in non-native speech.

But language is not only speech: when we have a conversation, we also move to the rhythm of our speech, for instance making simple up-and-down hand movements. These co-speech gestures typically co-occur with stressed syllables. How do language learners move when speaking their foreign language? In other words, do learners - next to having a foreign accent in their speech - also show a ‘kinematic accent’ in their co-speech hand movements?

How did you test this?

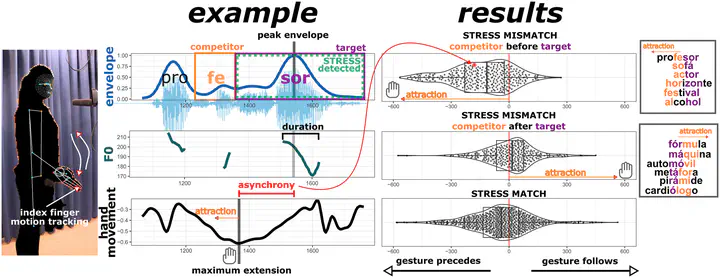

We recorded Dutch learners of Spanish, producing Spanish words that are very similar in their two languages, such as Spanish pro-fe-SOR (vs. Dutch pro-FES-sor). We asked them to make a simple up-and-down hand movement on each of the words. Using motion-tracking, we then measured the timing of their hand movements.

The motion-tracking record showed that, even when our Dutch learners correctly said pro-fe-SOR (with final stress), their hand movements were slightly ’early’, falling closer to the syllable that’s stressed in Dutch (pro-FES-sor; top panel in figure above). Similarly, in words like MÁ-qui-na (Dutch: ma-CHI-ne), the hand movements were relatively ’late’, reflecting the Dutch stress pattern (middle panel in figure above).

Why is this important?

Most of the research on gesture-speech alignment (how we move and gesture when we speak) points towards close synchrony between our hands and voice. Our study is one of the first examples of gesture-speech asynchrony, whereby the native language influences not only how you speak (foreign accent) but also how you move (kinematic accent). Whether the ‘kinematic accent’ is observable for native speakers and influences their impressions of nativelikeness (like a foreign accent does) remains an intriguing question for future research. Consequently, our finding is important for language learners, who do not only need to learn new pronunciations, but also how to ‘move in a foreign language’.

Full reference

This paper forms the final output of a team science project, with all team members sharing first authorship. It was incredibly inspiring to learn from each other’s expertise, in a supportive atmosphere, and so much fun to celebrate the final outcome. The full citation, open access PDF, and all data are publicly available from the links below:

(2026). Foreign language learners show a kinematic accent in their co-speech hand movements. Open Mind, 10, 66-78, doi:10.1162/OPMI.a.321.